METROPARK, N.J. -- I love train travel, the excitement of going somewhere far away and new. We once took a train from Chicago to Seattle, sleeping in pull-down bunks and eating in a dining car with white linen table clothes as we rode through Glacier National Park. I live a block from a train line, and sometimes when I hear the whistle, I feel a tinge of jealousy that while I’m about to go grocery shopping, someone inside the train is embarking on an adventure, if only to New York City.

But last weekend, it was me who was off on an adventure, to a writing conference in Boston. I got to the train station in Metropark 30 minutes early, fearing there would be no spaces left in the parking garage. And I went up to the platform 15 minutes early, fearing there would be no seats left on the train. I approach situations like this from a place of scarcity, like it’s a big game of musical chairs, and when the train doors open, everyone will rush in and find a seat, and I will be left without one. It’s enough to raise my heart rate.

It doesn’t end there. Once I’ve found a seat, I relax for a moment before I’m overcome by the notion that I want the whole two-seat row to myself. A train is a very small space with a lot of people. I’m sure we would all get along smashingly if everyone could have their own row, from which we could chat and have drinks and eat cheese, but you’re often forced to share your small row with someone who is loud or eating chips or takes up more than their fair share of the seating real estate. A man with unusually wide elbows once sat next to me, and he seemed oblivious to the fact that he was crossing that invisible line between the two seats and commandeering the arm rest. I would wait for him to remove his arm for a moment, to turn a page or adjust his eyeglasses, and as soon as he did, I would plant my elbow on the arm rest, myself, as if to say, you’re not the boss of it.

At Metropark, I was first to get on the train, but there’s really no benefit in getting there before the others. There will always be people who come in after you, and eye the empty seat next to yours, as happened with a mother and her two young girls, one who was about five and an older one who was about seven. The mother nudged the younger girl into the empty seat next to me, and the girl reluctantly obliged, though she wouldn’t look in my direction, and every time I glanced over, all I could see was her high black pony tail in a red elastic band. She was wearing a pink sweat suit and a backpack that had a big pink smiley face and daisy-shaped zipper pulls. She refused to remove the backpack, which forced her to sit on the edge of her seat. When she leaned forward to see what her older sister was doing one row up, I saw the smiley face was actually the head of a butterfly and that there were two little blue antennae coming out of the top of it. She only looked in my direction a couple of times, when the curiosity about who she was sitting with was too great to bare.

Her mother sat across the aisle from her, and I kept thinking I should let the mother have my seat, so she could sit with her daughter, but I preferred to sit by the window, and hers was an aisle seat.

As we neared New York City, there was a lot of movement, as people gathered their belongings and headed toward the doors. Seats started to become available, and I could hear the woman directly in front of me say to the mother, “You can have these four seats, and I’ll move here, so your family can stay together.”

“Well, isn’t she a big man, offering her seat now that the train is half empty,” I thought.

I went to the bathroom quickly, before the new passengers from Penn Station could board. When I returned to my seat, the young girl with the caterpillar backpack had moved into a double seat with her older sister, who was licking a lollipop on her own terms, putting it in her mouth only once every couple of minutes. It made me wonder for how many years she’d had this lollipop.

I sat back down in my row and as the new passengers from Penn Station entered the train, I tried to puff myself up like a blowfish so that no one would want to sit with me. It’s not right to keep your bag on the seat next to you, but I kept it on the edge of my own seat so that it oozed over into the adjacent seat ever so slightly, giving the illusion that there was barely enough room for all of us and our gear to fit. There are some who see this game and resent it, taking a sinister pleasure in making you move your stuff because they know they can.

As the new passengers filed in, I felt relief every time one moved on without stopping, especially the man who kept sneezing. By the time we got through the tunnel between Upper Manhattan and the Bronx, I was able to exhale and dropped down the tray table of the seat next to me so I could spread myself out. This must be how it feels to be rich, I thought. A space to one’s self. With my coffee on the tray table next to me, I relaxed and looked out the window.

By the time the train cleared the Bronx, passengers had settled in. The girl who had gallantly offered her seat to the woman with the two young girls was still sitting in front of me and talking on her phone. People on public transportation seem to have a keen awareness of those next to them and in front of them, but they don’t realize just how close the person behind them is. I had no choice but to feel I was an integral part of their conversation. We were talking about someone from her office, who had become problematic.

“Well, if she doesn’t shut her fucking mouth,” the woman told us, and then continued, “And if she’s going to be shitty, I can be shitty, too. She doesn’t know when to stop. She just doesn’t know when to stah-ahp.”

I was reluctant to give her any advice, particularly because I wasn’t asked.

Comfortable they could handle this situation without me, I decided to go to the dining car for some egg bites and a coffee, and as I walked back to my car, I overheard a passenger telling two conductors about a man in her car who was having a phone conversation on speakerphone.

“I don’t want to be annoying, but I don’t know if he realizes how loud he is,” the woman told the conductors. Apparently, it’s epidemic.

Back in my train car, I saw the young girl with the caterpillar backpack leaning toward her sister, telling her something vitally important. Her sister gave her lollipop a single lick.

The car was noticeably quiet, and I realized the loud girl was gone, having descended the steps in some Connecticut town, boots stomping on the ground, possibly heading toward the object of her derision, ready to fucking fuck her the fuck up.

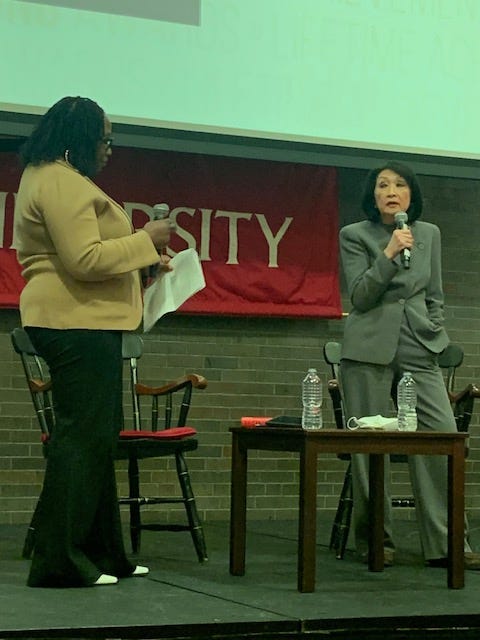

The conference in Boston was good but went by too quickly. I saw old friends, learned writing tips and heard keynotes from journalism legends like Susan Orlean and Connie Chung. Before long, I was heading back to the train, but this time, I was not anxious about having a seat. In fact I got to the station with just 15 minutes to spare. That’s because I bought a reserved seat this time. It was available for just $10 more.

I was a cool customer, making my way down to the platform just five minutes before the train’s departure. It was freeing, not unlike the freedom I feel when I check my luggage at the airport. When I have carry-on, I get so anxious that there won’t be any overhead compartments left by the time my group, usually group 16, is called that I try to blend into group 3 or 4, thinking I’d rather get yelled at by the flight attendant and get tossed back to group 16 than risk not having an overhead compartment for my bag.

But a reserved seat does not guarantee peace and solitude, as I saw when I got on the train and found my reservation was in a bank of four seats set around a table, and I was sitting with a young student with Air Pods and a mac computer and a giant cup of green Matcha, all of which he had spread out on his side of the table. After about 20 minutes, he accidentally hit the cup, sending green juice flowing on to his computer and his phone (Apparently, the landscape of Rhode Island was tilted in my favor because the juice remained on his side). The two of us began searching frantically for a napkin. I found one in my jacket pocket and began dabbing the puddle that was on his phone while he tipped his laptop upside down, trying to get the liquid out of his keyboard. He then mopped it up with his shirt.

“Thank you so much. You are so nice. So so nice,” he said.

“Ach,” I said.

About an hour later, a faint smell of burning rubber wafted through the train car that was clearly coming from outside, but when he bent down to smell his keyboard, thinking the Matcha was causing it to short circuit, I found it endearing. And when shortly thereafter, he cleaned up all his wrappers and cups and got off the train, I felt a tiny loss, as the bond we made — tenuous as it was — was abruptly broken.

Another funny piece with heart.

As an Amtrak semi-regular, I can picture the various scenes. This afternoon, I'll be heading down to Philadelphia on the Acela, which is usually a bit more comfortable, if less amusing. More interesting than the mode of travel is the event I'm heading to: my brother has asked me to go with him to a Jimi Hendrix tribute show down in Atlantic City (where, to quote Bruce Springsteen, "everything that dies someday comes back"). In itself, that's of no particular moment, but it's better seen as the bookend to the musical event I went to last night, "The Threepenny Opera," at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. I am willing to bet I am the only person on earth to hit that particular exacta.